Hy in African Art Many Cultures Represent the Head of a Figure as Larger Than the Rest of the Body

The elevation famous sculptures of all fourth dimension

From pre-history to the 21st century, here are the meridian famous sculptures of all fourth dimension

Unlike a painting, sculpture is iii dimensional art, allowing you to view a piece from all angles. Whether jubilant an historic figure or created equally a work of art, sculpture is all the more powerful due to its physical presence. The top famous sculptures of all fourth dimension are instantly recognizable, created past artists spanning centuries and in mediums ranging from marble to metallic.

Like street fine art, some works of sculpture are large, assuming and unmissable. Other examples of sculpture may be delicate, requiring close report. Right here in NYC, you can view important pieces in Central Park, housed in museums like The Met, MoMA or the Guggenheim, or every bit public works of outdoor fine art. Most of these famous sculptures tin be identified by even the most casual viewer. From Michaelangelo's David to Warhol's Brillo Box, these iconic sculptures are defining works of both their eras and their creators. Photos won't do these sculptures justice, so whatsoever fan of these works should aim to see them in person for total result.

Superlative famous sculptures of all time

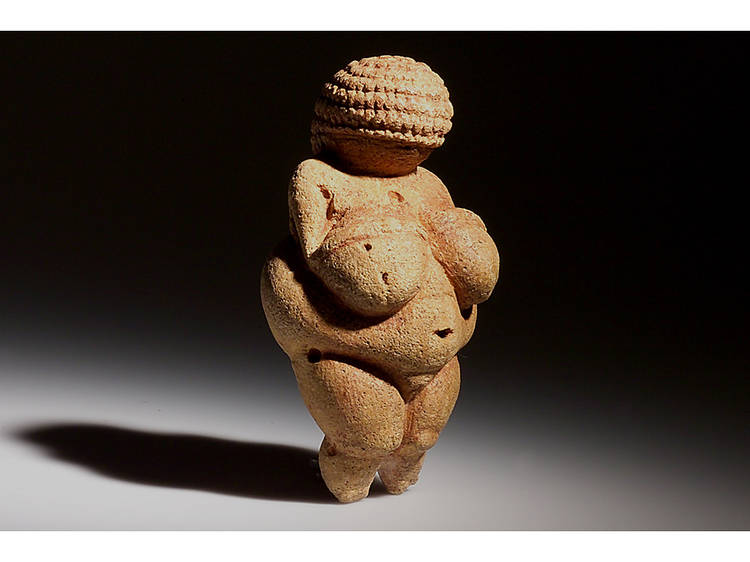

one. Venus of Willendorf, 28,000–25,000 BC

The ur sculpture of art history, this tiny figurine measuring but over four inches in acme was discovered in Austria in 1908. Nobody knows what office it served, but guesswork has ranged from fertility goddess to masturbation aid. Some scholars suggest it may have been a cocky-portrait made by a woman. It'south the most famous of many such objects dating from the Old Stone Age.

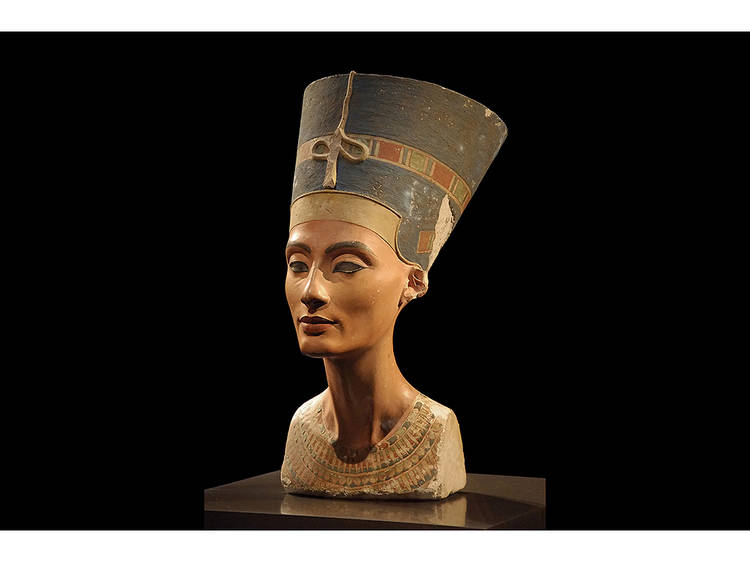

2. Bust of Nefertiti, 1345 BC

This portrait has been a symbol of feminine beauty since it was first unearthed in 1912 within the ruins of Amarna, the capital metropolis built by the most controversial Pharaoh of Ancient Egyptian history: Akhenaten. The life of his queen, Nefertiti, is something of mystery: It's thought that she ruled every bit Pharaoh for a time after Akhenaten'southward death—or more probable, as the co-regent of the Boy King Tutankhamun. Some Egyptologist believe she was really Tut's mother. This stucco-coated limestone bust is thought to exist the handiwork of Thutmose, Akhenaten's court sculptor.

3. The Terracotta Army, 210–209 BC

Discovered in 1974, the Terra cotta Army is an enormous cache of clay statues buried in three massive pits well-nigh the tomb of Shi Huang, the first Emperor of Communist china, who died in 210 BC. Meant to protect him in the afterlife, the Army is believed by some estimates to number more than 8,000 soldiers along with 670 horses and 130 chariots. Each is life-size, though actual height varies according to military rank.

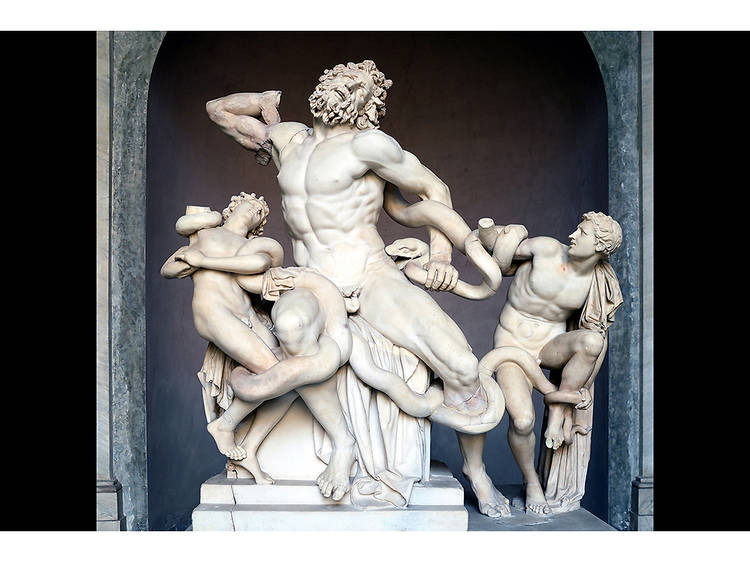

4. Laocoön and His Sons, Second Century BC

Perchance the about famous sculpture of Roman artifact, Laocoön and His Sons was originally unearthed in Rome in 1506 and moved to the Vatican, where it resides to this 24-hour interval. It is based on the myth of a Trojan priest killed along with his sons by sea serpents sent past the bounding main god Poseidon as retribution for Laocoön's try to expose the ruse of the Trojan Horse. Originally installed in the palace of Emperor Titus, this life-size figurative group, attributed to a trio of Greek sculptors from the Island of Rhodes, is unrivaled as a study of human suffering.

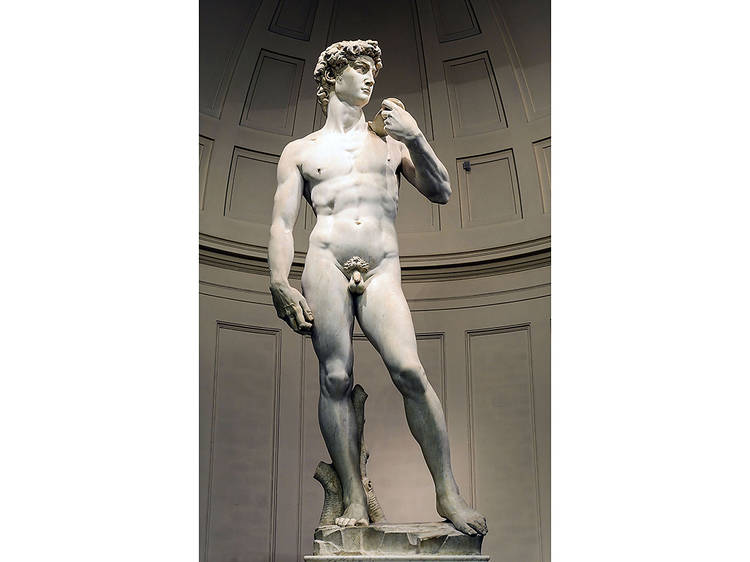

5. Michelangelo, David, 1501-1504

I of the most iconic works in all of art history, Michelangelo's David had its origins in a larger project to decorate the buttresses of Florence's not bad cathedral, the Duomo, with a grouping of figures taken from the Old Testament. The David was one, and was actually begun in 1464 past Agostino di Duccio. Over the next two years, Agostino managed to rough out role of the huge block of marble hewn from the famous quarry in Carrara before stopping in 1466. (No i knows why.) Another creative person picked upwards the slack, simply he, too, simply worked on it briefly. The marble remained untouched for the next 25 years, until Michelangelo resumed carving information technology in 1501. He was 26 at the time. When finished, the David weighed six tons, pregnant it couldn't be hoisted to the cathedral'due south roof. Instead, it was put on display merely outside to the entrance to the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence's town hall. The figure, i of the purest distillations of the High Renaissance fashion, was immediately embraced past the Florentine public every bit a symbol of the city-state'southward own resistance against the powers arrayed against it. In 1873, the David was moved to Accademia Gallery, and a replica was installed in its original location.

half-dozen. Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–52

Acknowledged every bit an originator of the High Roman Baroque style, Gian Lorenzo Bernini created this masterpiece for a chapel in the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria. The Baroque was inextricably linked to the Counter-Reformation through which the Catholic Church tried to stem the tide of Protestantism surging across 17th-century Europe. Artworks similar Bernini's was function of the program to reaffirm Papal dogma, well served hither by Bernini'southward genius for imbuing religious scenes with dramatic narratives. Ecstasy is a case in betoken: Its subject field—Saint Teresa of Ávila, a Spanish Carmelite nun and mystic who wrote of her run across with an angel—is depicted only equally the angel is about to plunge an arrow into her heart. Ecstasy'southward erotic overtones are unmistakable, nigh apparently in the nun's orgasmic expression and the writhing fabric wrapping both figures. An architect equally all as an artist, Bernini also designed the setting of the Chapel in marble, stucco and paint.

seven. Antonio Canova, Perseus with the Head of Medusa, 1804–6

Italian artist Antonio Canova (1757–1822) is considered to be the greatest sculptor of the 18th-century. His work epitomized the Neo-Classical style, every bit y'all tin can come across in his rendition in marble of the Greek mythical hero Perseus. Canova actually fabricated two versions of the piece: One resides at the Vatican in Rome, while the other stands in the Metropolitan Museum of Art'southward European Sculpture Court.

viii. Edgar Degas, The Little Fourteen-Twelvemonth-Onetime Dancer, 1881/1922

While Impressionist master Edgar Degas is all-time known as a painter, he too worked in sculpture, producing what was arguably the most radical endeavour of his oeuvre. Degas fashioned The Little 14-Twelvemonth-Old Dancer out of wax (from which subsequent bronze copies were cast later his decease in 1917), but the fact that Degas dressed his eponymous subject in an bodily ballet costume (complete with bodice, tutu and slippers) and wig of existent pilus caused a sensation when Dancer debuted at the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition of 1881 in Paris. Degas elected to embrace most of his embellishments in wax to lucifer the rest of girl's features, but he kept the tutu, equally well as a ribbon tying backing her hair, every bit they were, making the figure one of the outset examples of found-object fine art. Dancer was the only sculpture that Degas exhibited in his lifetime; after his death, some 156 more than examples were found languishing in his studio.

9. Auguste Rodin, The Burghers of Calais, 1894–85

While most people associate the bully French sculptor Auguste Rodin with The Thinker, this ensemble commemorating an incident during the Hundred Years' State of war (1337–1453) between Britain and France is more important to the history of sculpture. Commissioned for a park in the metropolis of Calais (where a year-long siege past the English in 1346 was lifted when six town elders offered themselves up for execution in substitution for sparing the population), The Burghers eschewed the format typical of monuments at the time: Instead of figures isolated or piled into a pyramid atop a tall pedestal, Rodin assembled his life-size subjects directly on the ground, level with the viewer. This radical move toward realism broke with the heroic treatment unremarkably accorded such outdoor works. With The Burghers, Rodin took one of the first steps toward mod sculpture.

10. Pablo Picasso, Guitar, 1912

In 1912, Picasso created a cardboard maquette of a slice that would have an outsized impact on 20th-century art. Also in MoMA's collection, information technology depicted a guitar, a discipline Picasso often explored in painting and collage, and in many respects, Guitar transferred collage'due south cutting and paste techniques from two dimensions to three. It did the aforementioned for Cubism, as well, by assembling flat shapes to create a multifaceted form with both depth and volume. Picasso's innovation was to eschew the conventional etching and modeling of a sculpture out of a solid mass. Instead, Guitar was fastened together like a structure. This thought would reverberate from Russian Constructivism down to Minimalism and across. Two years afterward making the Guitar in cardboard, Picasso created this version in snipped tin can.

11. Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913

From its radical beginnings to its concluding fascist incarnation, Italian Futurism shocked the earth, but no single work exemplified the sheer delirium of the motion than this sculpture past one of its leading lights: Umberto Boccioni. Starting out every bit a painter, Boccioni turned to working in three dimensions after a 1913 trip to Paris in which he toured the studios of several advanced sculptors of the menstruum, such as Constantin Brancusi, Raymond Duchamp-Villon and Alexander Archipenko. Boccioni synthesized their ideas into this dynamic masterpiece, which depicts a striding figure set in a "synthetic continuity" of movement equally Boccioni described it. The piece was originally created in plaster and wasn't cast in its familiar bronze version until 1931, well later on the artist'due south death in 1916 equally a member of an Italian artillery regiment during Globe State of war I.

12. Constantin Brancusi, Mlle Pogany, 1913

Born in Romania, Brancusi was one of most important sculptors of early on-20th century modernism—and indeed, one of the most important figures in the entire history of sculpture. A sort of proto-minimalist, Brancusi took forms from nature and streamlined them into abstruse representations. His style was influenced past the folk art of his homeland, which frequently featured vibrant geometric patterns and stylized motifs. He also fabricated no distinction between object and base, treating them, in sure cases, as interchangeable components—an approach that represented a crucial intermission with sculptural traditions. This iconic piece is a portrait of his model and lover, Margit Pogány, a Hungarian art student he met in Paris in 1910. The start iteration was carved in marble, followed by a plaster copy from which this bronze was fabricated. The plaster itself was exhibited in New York at the legendary Armory Bear witness of 1913, where critics mocked and pilloried information technology. But information technology was as well the most reproduced slice in the show. Brancusi worked on various versions of Mlle Pogany for some xx years.

13. Duchamp, Cycle Wheel, 1913

Cycle Bike is considered the offset of Duchamp's revolutionary readymades. However, when he completed the slice in his Paris studio, he really had no thought what to call it. "I had the happy idea to fasten a bicycle bike to a kitchen stool and watch it plough," Duchamp would after say. It took a 1915 trip to New York, and exposure to the city's vast output of manufactory-built goods, for Duchamp to come with the readymade term. More importantly, he began to see that making fine art in the traditional, handcrafted manner seemed pointless in the Industrial Historic period. Why carp, he posited, when widely available manufactured items could do the chore. For Duchamp, the thought backside the artwork was more of import than how it was made. This notion—perchance the kickoff real example of Conceptual Art—would utterly transform art history going forward. Much like an ordinary household object, yet, the original Bike Wheel didn't survive: This version is really a replica dating from 1951.

14. Alexander Calder, Calder's Circus, 1926-31

A beloved fixture of the Whitney Museum's permanent collection, Calder's Circus distills the playful essence that Alexander Calder (1898–1976) brought to conduct every bit an creative person who helped to shape 20th-sculpture. Circus, which was created during the creative person'southward time in Paris, was less abstract than his hanging "mobiles," but in it'due south own style, information technology was just equally kinetic: Made primarily out of wire and wood, Circus served equally the centerpiece for improvisational performances, in which Calder moved around diverse figures depicting contortionists, sword swallowers, lion tamers, etc., like godlike ringmaster.

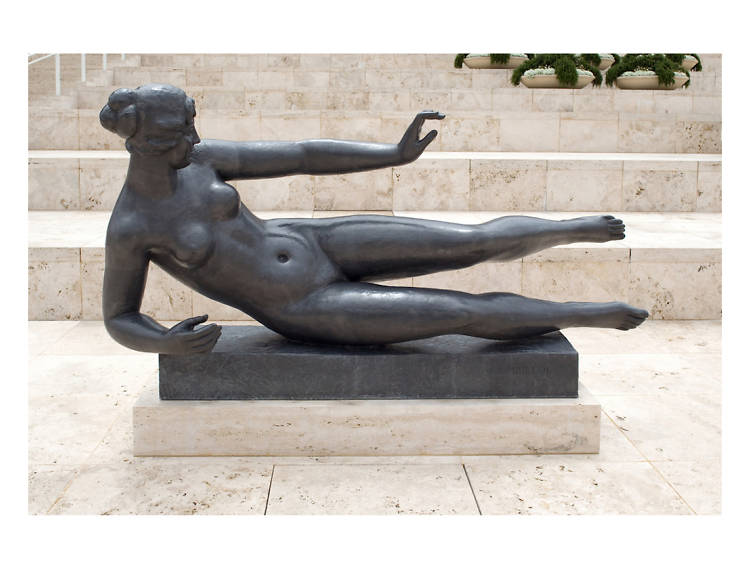

15. Aristide Maillol, L'Air, 1938

As painter and tapestry designer as well as a sculptor, French artist Aristide Maillol (1861–1944) could exist best described as a modernistic Neo-Classicist who put a streamline, 20th-century spin on traditional Greco-Roman bronze. He could also exist described as a radical bourgeois, though it should be remembered that even avant-garde contemporaries like Picasso produced works in an accommodation of Neo-Classical mode later World War I. Maillol'due south subject was the female nude, and in L'Air, he's created a contrast between the fabric mass of his bailiwick, and the style she appears to exist floating in space—balancing, as it were, obdurate physicality with evanescent presence.

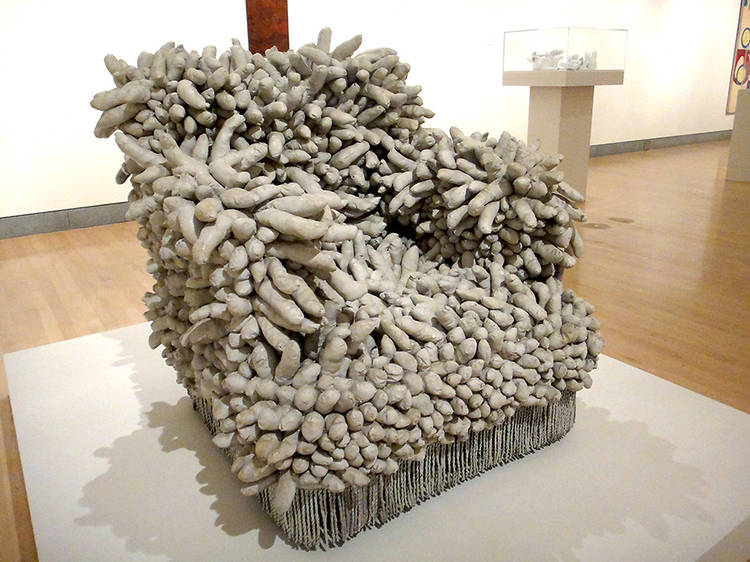

sixteen. Yayoi Kusama, Aggregating No one, 1962

A Japanese artist who works in multiple mediums, Kusama came to New York in 1957 returning to Nihon in 1972. In the interim, she established herself as a major figure of the downtown scene, one whose art touched many bases, including Pop Fine art, Minimalism and Functioning Fine art. Equally a woman artist who often referred to female sexuality, she was also a forerunner of Feminist Art. Kusama'south work is often characterized by hallucinogenic patterns and repetitions of forms, a proclivity rooted in certain psychological weather—hallucinations, OCD—she's suffered since childhood. All of these aspects of Kusuma's art and life are reflected in this work, in which an ordinary, upholstered piece of cake chair is unnervingly subsumed past a plaguelike outbreak of phallic protuberances fabricated of sewn blimp fabric.

17. Marisol, Women and Domestic dog, 1963-64

Known just by her showtime name, Marisol Escobar (1930–2016) was built-in in Paris to Venezuelan parents. As an artist, she became associated with Pop Art and later Op Art, though stylistically, she belonged to neither group. Instead, she created figurative tableaux that were meant as feminist satires of gender roles, celebrity and wealth. In Women and Dog she takes on the objectification of women, and the way that male-imposed standards of femininity are used to force them to adapt.

eighteen. Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (Soap Pads), 1964

The Brillo Box is perchance the best known of a serial of sculptural works Warhol created in the mid-'60s, which effectively took his investigation of popular culture into 3 dimensions. True to the name Warhol had given his studio—the Factory—the artist hired carpenters to work a kind of assembly line, nailing together wooden boxes in the shape of cartons for various products, including Heinz Ketchup, Kellogg's Corn Flakes and Campbell's Soup, as well Brillo soap pads. He so painted each box a color matching the original (white in the case of Brillo) before adding the product name and logo in silkscreen. Created in multiples, the boxes were oftentimes shown in large stacks, effectively turning any gallery they were in into a high-cultural facsimile of a warehouse. Their shape and serial production was perchance a nod to—or parody of—the so-nascent Minimalist style. Simply the existent point of Brillo Box is how its close approximation to the real thing subverts artistic conventions, past implying that at that place's no real difference between manufactured goods and work from an artist'due south studio.

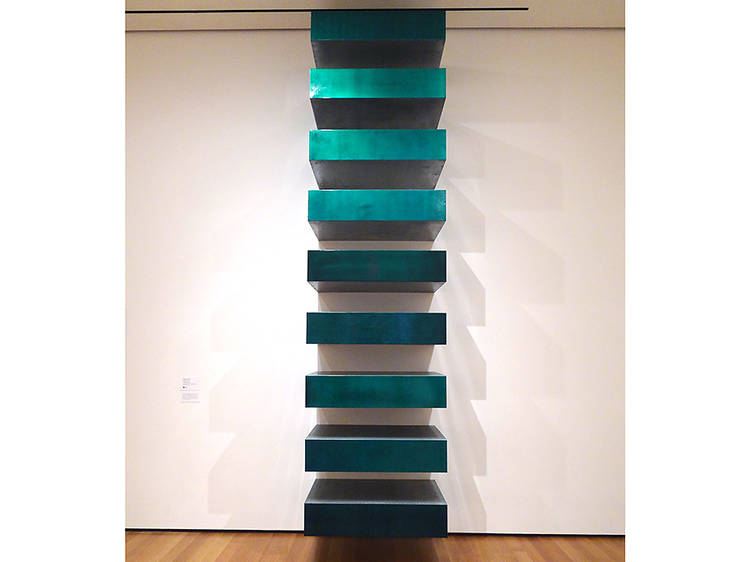

19. Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack), 1967

Donald Judd's name is synonymous with Minimal Art, the mid-'60s motility that distilled modernism's rationalist strain to blank essentials. For Judd, sculpture meant articulating the piece of work'south physical presence in infinite. This idea was described by the term, "specific object," and while other Minimalists embraced it, Judd arguably gave the thought its purest expression by adopting the box as his signature form. Like Warhol, he produced them as repeating units, using materials and methods borrowed from industrial fabrication. Dissimilar Warhol's soup cans and Marilyns, Judd'south art referred to zip exterior of itself. His "stacks," are among his all-time-known pieces. Each consists of a group of identically shallow boxes made of galvanized canvass metal, jutting from the wall to create a cavalcade of evenly spaced elements. But Judd, who started out equally a painter, was but as interested in colour and texture as he was in form, as seen hither by greenish-tinted auto-body lacquer applied to the front face of each box. Judd's interplay of color and material gives Untitled (Stack) a fastidious elegance that softens its abstract absolutism.

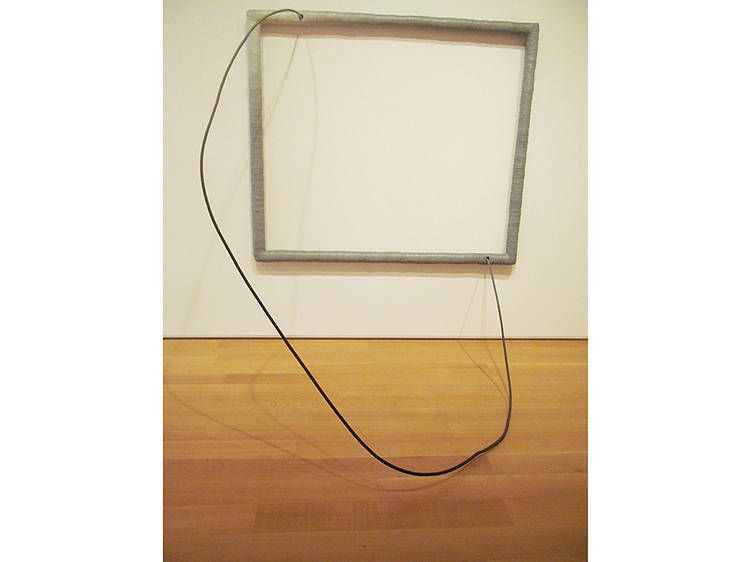

xx. Eva Hesse, Hang Up, 1966

Like Benglis, Hesse was a woman artist who filtered Postminimalism through an arguably feminist prism. A Jew who fled Nazi Deutschland as a child, she explored organic forms, creating pieces in industrial fiberglass, latex and rope that evoked peel or flesh, genitals and other parts of the torso. Given her groundwork, it's tempting to detect an undercurrent of trauma or anxiety in works such as this one.

21. Richard Serra, One Ton Prop (House of Cards), 1969

Following Judd and Flavin, a group of artists departed from Minimalism's artful of clean lines. As part of this Postminimalist generation, Richard Serra put the concept of the specific object on steroids, vastly enlarging its scale and weight, and making the laws of gravity integral to the thought. He created precarious balancing acts of steel or atomic number 82 plates and pipes weighing in the tons, which had the effect of imparting a sense of menace to the piece of work. (On ii occasions, riggers installing Serra pieces were killed or maimed when the work accidentally collapsed.) In recent decades, Serra's work has adopted a curvilinear refinement that'southward fabricated it hugely pop, but in the early going, works like I Ton Prop (House of Cards), which features 4 lead plates leaned together, communicated his concerns with barbarous directness.

22. Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970

Following the full general countercultural trend during the 1960s and 1970s, artists began to defection against the commercialism of the gallery world, developing radically new art forms similar earthworks. Also known as state art, the genre's leading figure was Robert Smithson (1938–1973), who, forth with artists such as Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and James Turrel, ventured into the deserts of the Western The states to create awe-inspiring works that acted in concert with their surroundings. This site-specific approach, as it came to be called, oft employed materials taken directly from the mural. Such is the case with Smithson's Spiral Jetty, which juts into Utah's Great Common salt Lake from Rozel Point on the lake's northeastern shore. Made of mud, salt crystals and basalt extracted onsite, Spiral Jetty measures 1,500 by 15 anxiety. It was submerged nether the lake for decades until a drought in the early 2000s brought it to the surface again. In 2017, Spiral Jetty was named the official artwork of Utah.

23. Louise Conservative, Spider, 1996

The French-born artist's signature work, Spider was created in the mid-1990s when Conservative (1911-2010) was already in her eighties. It exists in numerous versions of varying scale, including some that are monumental. Spider is meant equally a tribute to the artist'south mother, a tapestry restorer (hence the allusion to the arachnid's propensity for spinning webs).

24. Antony Gormley, The Affections of the Due north, 1998

Winner of the prestigious Turner Prize in 1994, Antony Gormley is ane of the most historic contemporary sculptors in the UK, but he's also known the world over for his unique accept on figurative fine art, ane in which wide variations in calibration and style are based, for the near role, on the aforementioned template: A bandage of the creative person's own body. That'south true of this enormous winged monument located most the boondocks of Gateshead in northeastern England. Sited along a major highway, Angel soars to 66 feet in elevation and spans 177 feet in width from wingtip to wingtip. According the Gormley, the work is meant as a sort of symbolic marker between Britain's industrial past (the sculpture is located in the England's coal state, the eye of the Industrial Revolution) and its post-industrial hereafter.

25. Anish Kapoor, Cloud Gate, 2006

Affectionately called "The Bean" by Chicagoans for its aptitude ellipsoidal form, Cloud Gate, Anish Kapoor's public art centerpiece for the Second City'due south Millennium Park, is both artwork and architecture, providing an Instagram-set up entrance for Dominicus strollers and other visitors to the park. Fabricated from mirrored steel, Deject Gate's fun-firm reflectivity and big-scale makes it Kapoor'due south best-known piece.

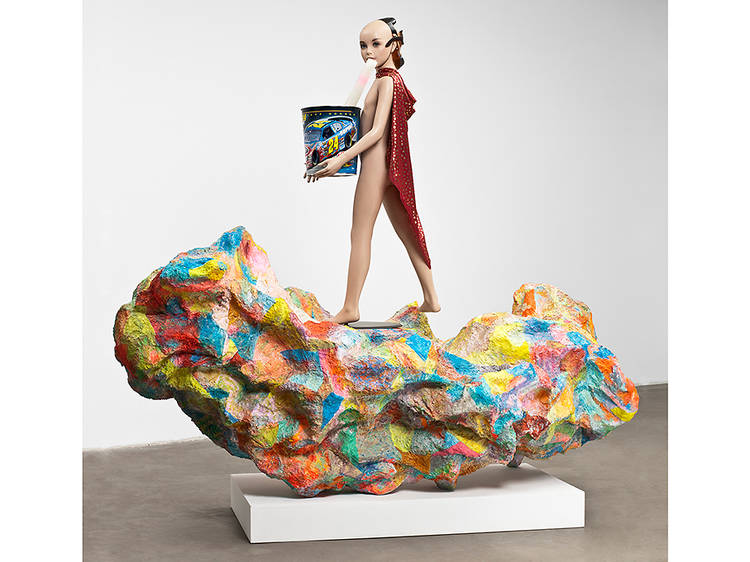

26. Rachel Harrison, Alexander the Nifty, 2007

Rachel Harrison's work combines a consummate ceremonial with a knack for imbuing seemingly abstract elements with multiple meanings, including political ones. She fiercely questions monumentality and the masculine prerogative that goes with it. Harrison creates the bulk of her sculptures by stacking and arranging blocks or slabs of Styrofoam, earlier covering them in a combination of cement and painterly flourishes. The cherry on pinnacle is some sort of establish object, either alone or in combination with others. A prime case is this mannequin atop an elongated, paint-splashed form. Wearing a cape, and a backwards-facing Abraham Lincoln mask, the work sends up the great human theory of history with its evocation of the Aboriginal Earth's conqueror standing alpine on a clown-colored stone.

Check out Picasso's best paintings

An e-mail you'll really dearest

🙌 Awesome, you lot're subscribed!

Thanks for subscribing! Look out for your first newsletter in your inbox before long!

Source: https://www.timeout.com/newyork/art/top-famous-sculptures-of-all-time

0 Response to "Hy in African Art Many Cultures Represent the Head of a Figure as Larger Than the Rest of the Body"

Post a Comment